The ten chapters of the book follow exactly the outline of the ten television shows. Perhaps for this reason, among others, some critics on the Left have voiced the hope that not many people will read the book unfortunately for them, Free to Choose-like William Simon’s untouted A Time for Truth two years ago-is assaulting the top of the best-seller lists. Reading the Friedmans is not a free lunch. The statistics they offer are fascinating, since they usually challenge the conventional wisdom and one has to linger over them to absorb them, but this makes the book slow going.

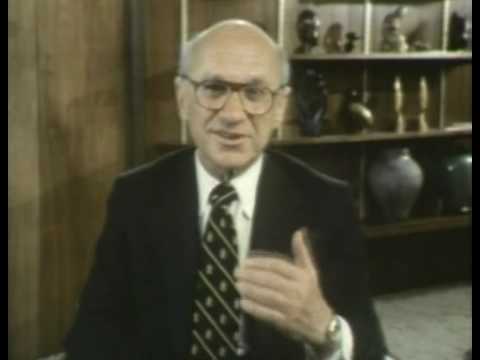

The Friedmans do not write with the elegance or wit of Professor Galbraith, and they load chapter after chapter, like freight cars, with heavy burdens of fact. In tone of voice, intellectual bent, and style of argument, Milton Friedman seems like “one of us.” Where did he-or we-go wrong? Watching Friedman on television was, for me, a sort of journey of self-criticism.Īs engaging as the television shows are, the book that accompanies them is more difficult. Arguing as the viewer must with Friedman is not like arguing with the Chamber of Commerce. They are at times even startling, since those of us who grew up in the democratic-socialist tradition have not often had to confront an effective champion of capitalism. Friedman’s English retains traces of the accents of working-class New York he strives for plainness and street sense. There is about him none of the hauteur of John Kenneth Galbraith. He is smaller and looks far more vulnerable than I had expected. So it surprised me to encounter Milton Friedman, the man, on television in his recent series on PBS called, like the book he has written with his wife, Free to Choose.

The censors of the Left always spoke his name in a certain way: an ideologue, trapped in abstractions, out of touch with reality-dangerous, too.

Milton Friedman is the economist my intellectual mentors warned me against.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)